Human Health & Climate Change

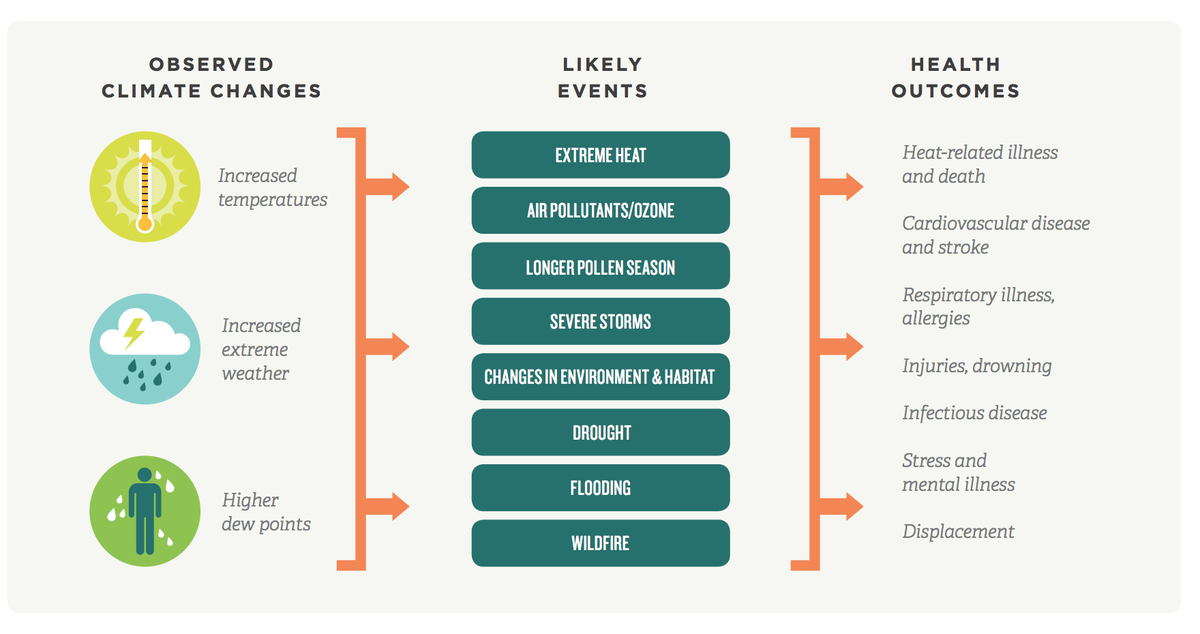

There are at least five major climate-related hazards that directly affect human health: extreme heat, flooding, drought, vector borne diseases, and air pollution.

Although we haven't yet seen a significant increase in extreme heatwaves in Minnesota, climate change is expected to increase the frequency and severity of both heatwaves and extreme weather. Across Minnesota, the number of days with temperatures above 90°F is projected to increase anywhere from 10 to 40 days per year by the 2100. Heatwaves can lead to dehydration, heat stroke and even death. They already affect Minnesotans' health in the present day:, but longer and hotter heatwaves will disproportionately affect the elderly and those with underlying health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease.

The record-breaking heatwave in the U.S. Pacific Northwest in June 2021 caused more than 600 excess deaths in one week in Washington and Oregon and was worsened by human-caused climate change.

Flooding is expected to also become more severe as "mega-rain" events occur more frequently. Flooding can lead directly to loss of life via drowning, or it can cause indirect harm by damaging health infrastructure (such as hospitals), causing water-borne disease outbreaks, or promoting mold growth.

68% of water-borne disease outbreaks in the U.S. between 1948 and 1994 occurred after heavy precipitation events.

Too much water can cause flooding, but too little water can lead to drought. Drought can directly affect human health by decreasing the availability and quality of drinking water, reducing crop yields, and degrading air quality.

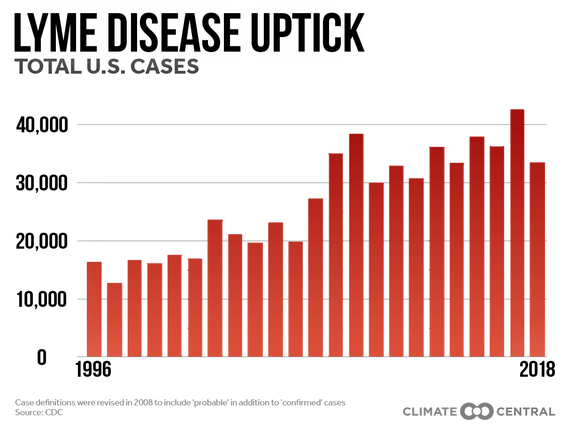

A warming climate also increases the risk of pest-borne illnesses. Longer growing seasons, increased humidity and overall warming can increase the geographic range of disease-carrying insects such as ticks and mosquitoes, leading to an increase in or emergence of new vector-borne illnesses.

Incidences of Lyme Disease in the U.S. doubled between 1991 and 2013.

(Figure: climatecentral.org)

Finally, climate change can lead to poor air quality through increased ozone production, longer allergen seasons, and suspension of microparticles that get into the respiratory system.

(Figure: Minnesota Environmental Quality Board)

References & Suggested Reading

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020: "Allergens and Pollen". URL

Curriero, F.C., et al., 2001: The association between extreme precipitation and waterborne disease outbreaks in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1194–1199. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1194

Ebi K.L., et al., 2008: Effects of global change on human health. In: Analyses of the Effects of Global Change on Human Health and Welfare and Human Systems. Report. URL.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2021: "Climate Change Indicators: Heat-Related Deaths." URL.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2021: "Climate Change Indicators: Lyme Disease." URL.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), 2021: "Ready: Floods". URL.

Harding, K. J., and P. K. Snyder, 2014: Examining future changes in the character of Central U.S. warm-season precipitation using dynamical downscaling. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 119. doi:10.1002/2014JD022575.

Harding, K. J., and P. K. Snyder, 2015: Using dynamical downscaling to examine mechanisms contributing to the intensification of Central U.S. heavy rainfall events. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 120. doi:10.1002/2014JD022819.

Melillo J., T. Richmond, and G. Yohe, 2014: An assessment from the U.S. Global Change Research Program to inform the public with scientific information and methods regarding climate change. Report.

Minnesota Environmental Quality Board, 2014: Minnesota and climate change: Our tomorrow starts today. Report.

Moss P., et al., 2017: Adapting to Climate Change in Minnesota: 2017. Report of the Interagency Climate Adaptation Team. Report. URL.

Popovich, N., and W. Choi-Schagrin, 2021: "Hidden Toll of the Northwest Heat Wave: Hundreds of Extra Deaths." The New York Times. URL.

USGCRP, 2018: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, 1515 pp. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.